You are probably quite aware of the fact that beer is made from malted barley, and that hops supply bitterness, aroma, and preservative properties to beer, but if you ask a number of laymen, "What is beer made from?", you will probably be astounded to learn of the number of people that give the simple reply, "hops", with no mention of malt or barley. A large number of people are quite unaware of the fact that the primary ingredient of beer (apart from water) is malted barley.

You are probably quite aware of the fact that beer is made from malted barley, and that hops supply bitterness, aroma, and preservative properties to beer, but if you ask a number of laymen, "What is beer made from?", you will probably be astounded to learn of the number of people that give the simple reply, "hops", with no mention of malt or barley. A large number of people are quite unaware of the fact that the primary ingredient of beer (apart from water) is malted barley.

Read also:

Ingredients for brewing: grain, sugar, malt extract

Traditional Commercial Brewing

Home Brewing. Beginners Start Here

All You should Know about Brewery Yeast

Home Brewing. Water and Water Treatment

Home Brewing. Mashing and Sparging

This is a hangover from the days, not so long ago, when thousands of people from London and Birmingham would go hop picking in Kent and Worcestershire for their annual paid holiday. When these people asked what the hops were used for, they were given the truthful reply "making beer". It would be logical for them to assume that hops were the primary ingredient of beer. Breweries use this lack of knowledge to advantage in their advertising. A number of beer adverts mention the quality or quantity of hops, but I have yet to see one that mentions barley. It is a strange fact that every year millions of people slush millions of gallons of beer down their throats without really knowing what is in it. If you mentioned barley to most beer drinkers they would stare at you in amazement, they would wonder what on earth barley had to do with beer! In fact, they would think that you were going lupulus!

Pollen records show the hop to be an English native plant, found mainly in fen woods and other moist woodland. Many books will tell you that hops were not used in beer in this country until the 15th century, but that is almost certainly not true. It is true, however, that there is no record of hops actually being cultivated in this country before 1428, but there are records of substantial quantities of hops being imported from the Netherlands before that date. A medieval carving showing hops, among other things, is in Southwell Minster, Nottingham. As the carving may represent some sort of harvest festival it could be conjectured that hops were cultivated in England in those times; although they may simply have been gathered from the wild.

The hop fruit has been found in late Anglo-Saxon deposits in The Hungate, York, and an eleventh century wooden boat exhumed from Graveney Marsh in Kent in the 1950s, radio-carbon dated at 1080, was found to have been carrying a cargo of hops. It is quite possible, considering its location, that this boat was bringing its cargo from the hop market at Hamburg, which was certainly in existence at that time. Science does not tell us in which direction the boat was travelling, or how long the boat was in use after being built, but it is curious that it was excavated near Faversham, on the doorstep of England's major hop growing region and just about the nearest seafall to Westbere near Canterbury; the area which, by legend, is supposed to be where the first hop gardens in England were sited. The possibility exists that hops have been cultivated in East Kent for much longer than is generally believed. The hop was certainly an important fruit and item of trade as long ago as the eleventh century.

The boat may have been delivering to a monastery. It is known that Benedictine monks in Germany were making hopped beer as early as 852. It is fair to assume that Benedictine monks in this country were also making hopped beer. They were certainly brewing by 1000.

Humulus lupulus

The hop plant Humulus lupulus is a hardy perenial climbing plant which is cultivated for beer making in parts of Kent, Hampshire, Worcestershire and Herefordshire. It can grow to as high as thirty feet, but the growth of cultivated hops is deliberately restricted to heights of between fifteen and eighteen feet depending upon variety; the heights at which they provide the best yield.

In the old days of manual hop picking the heights were restricted to about ten feet. The roots of a hop plans can go as deep as twelve feet. After the harvest at the end of each season the plants are cut down to their roots and the rootstock is left in the ground to overwinter. New shoots begin to appear on the rootstock during April and the strongest looking bines are selected for growth, the weaker ones being pruned away. The plants are trained to grow up strings that are supported from an overhead system of wires. There are usually three or four strings per plant, and usually two bines are allowed to grow up each string. The plants grow very rapidly indeed; from the end of April until about mid June the hop grows from rootstock to the top of the support wires, about eighteen feet.

The hop is dioecious, meaning that the male and female flowers are formed on different plants. Only the female plant is used in the making of beer. The plant can be fertilised or unfertilised although fertilised plants arethe norm in England. Obviously, only the fertilised plants produce seeds, but it matters not for the purpose of brewing whether the hop contains seeds or not. However, seeded plants are richer in lupulins (beta acids) and certain oils and are considered by English brewers to be superior in terms of flavour and aroma to their unseeded counter-parts. Continental brewing practice favours unseeded hops. Seeded hops usually have a lower yield of humulins (alpha acid) per acre in than unseeded hops. To ensure that the plant is fertilised by a known strain which is not going to affect the quality of the hop, the hop farmer places a number of male plants on the windward side of his hop garden.

The very rapid growth of the hop plant makes heavy demands on the soil, so the soil is enriched with a fertiliser which provides potassium, nitrogen, calcium and phosphates in the ratios of about 10:10:5:1. In the past, manure, cloth, and wood ash were traditionaly used as fertilisers.

Around the beginning of September the hops are ready for picking. The hops must be picked as soon as they are ready, just before they fully ripen. In the past it was common for vast armies of Londoners and Brummies to descend upon the hop growing areas of Kent and Worcestershire respectively to pick the hops. In these more modern times the hops are picked by machines, and thousands of people are deprived of their traditional paid annual holiday.

After picking, the hops need to be dried to a moisture content of about fifteen percent. This was traditionally done in the round oast houses that are a familiar sight around the lanes of Kent.

The hops were dried by warm air passing up through the perforated drying room floor, the air being heated by a charcoal fire situated under the floor. The hops were dried by maintaining them at temperature of 60 degrees C for a period of about ten hours, a steady draught was maintained through the hops by means of a rotating, right angled chimney which always faced away from the prevailing wind, creating a suction. The flow rate could be controlled by opening or closing ventilators situated in the base of the oast house. Traditionally the hops were sulphured by burning rock sulphur in the fire. This was done to ensure that the hops remain stable and pest free during storage.

On the domestic front, male hops can often be seen in targe ornamental gardens, grown for decorative reasons over archways and porches. Male hops are used because they do not smell of hop, as does the female plant. Their fast growth make them particularly useful in quickly establishing a new garden and they make an excellent summer windbreak if trained along wires or fence.

Pests and diseases of the hop

The hop farmer is probably the richest farmer in Britain, but he is also the most likely to face financial ruin. The rewards from hop growing are high, but so are the risks. Crop failures are frequent either because of inclement weather or because of attack by pest and diseases. The price of hops can fluctuate wildly from season to season depending upon the surpluses and shortages caused by the success or failure of the world's hop harvest, and variations in quality experienced from year to year. Improvements in storage techniques have levelled out some of the problems of hop shortages; the brewer is now able to take advantage of seasons where hops are of good quality and plentiful. But the disadvantage to the grower is that if the quality of his harvest is bad, his hops no longer get purchased, whereas previously the brewers often had no choice but to buy them, albeit at a lower price, because they were all that were available.

A hop garden takes three years to become established, and once established has a life of up to twenty years. Therefore the hop farmer does not have the advantages of crop rotation available to other farmers. He can suffer from a number of endemic soil-borne diseases and insect pests which have built up over centuries of intensive hop farming. These pests and diseases are almost impossible to eradicate completely once they become established. The hop farmer is continually fighting a battle against nature; battling against fungal diseases, viral diseases, and insect pests.

Verticillum Wilt and Downy Mildew are the most serious of the fungal diseases because they are capable of destroying the crop completely. By the time the infection has been detected it is usually too late to save the plant. These diseases winter in the soil, enter the roots of the plant and travel up its vascular system to the leaves in the summer. The leaves then die and fall off, thereby returning the disease back to the ground to begin its evil work again next year. Powdery mildew is another infection that is a headache to the hop farmer. It can affect plants during cultivation or in storage. It can be controlled if detected soon enough, but will destroy the brewing value of the plant if it is not tackled immediately it is detected. It is sensitive to sulphur, which was one of the earliest remedies. The original reason for sulphuring the harvested hops, by burning rock sulphur in the kiln during drying, was to ensure that mildews and other pests where prevented from damaging the stock.

The hop farmer also has more than his fair share of specially adapted insect pests to contend with. Green fly, lice (blight), red spider mite, wireworm, hop root weevil, hop flea beetle, and the damson hop aphid are a few of the many species of insect that attack the hop. Winged examples of these pests can quickly infect a whole region and transmit potentially lethal viral diseases, such as nettlehead, from plant to plant, and from garden to garden. Some of these insects lay their eggs in the soil, and can re-infest the garden year after year.

The classic among pests must be the damson hop aphid: The damson hop aphid not only seems to have adapted well to the hep, but also seems to have adapted nicely to life in Kent -the garden of England. It has two host plants; the hop and the damson, and it migrates freely between them for different stages of its life cycle. Also, it seems to realise that hops are cut down to their root-stock for winter, so, just before the harvest; the cunning blighter flies off to an orchard somewhere and lays its eggs on a damson tree. This frequent migration from hop garden to someone else's damson or plum orchard and back again makes control difficult.

Hop constituents

During the boil in the copper a complex series of reactions take place between the hops and the wort. These reactions are not fully understood, but they contribute to the flavour and aroma of the beer to a large degree, assist in the precipitation of trub, and provide some nutrients for the yeast. The most important constituents that are extracted from the hops during the boil are classified as alpha-acids (humulones), beta-acids (lupulones), and essential oils. The alpha-acids constitute the bittering power of the hop, the beta-acids have important side effects during the boil, and the essential oils constitute the flavour and aroma giving properties of the hop.

During the boil, the insoluble alpha-acids and beta-acids contained in the hops react with other constituents of the wort and are isomerised, that is, they are changed into a form that is readily soluble in water. Some of the essential oils are driven off during the boil and are lost and some other important hop constituents precipitate out of solution with the trub. This gives rise to the practice of sometimes adding hops to the wort in two or more stages and of sometimes adding hops to the beer after fermentation. This practice restores some of the components that have been driven off. Different properties of the hop are important at these different stages. This leads to the brewer classifying his hops into three categories, namely; Copper hops (or bittering hops), late hops (or aroma hops), and dry hops.

Copper hops (bittering hops)

Bittering hops are those which are put into the copper at the beginning of the boil to provide bitterness. Alpha-acid is the primary bittering ingredient of a hop, and it follows that hops with a high percentage of alpha-acid are the most economical copper hops, although any variety of hop can be used for bittering purposes. Indeed, high-alpha hops usually have a harsh flavour and a poor aroma. In general, the higher the alpha-acid content of the hop, the stronger its bittering is, but the poorer its flavour and aroma becomes. The highest quality beers use low-alpha hops for bittering such as Fuggles and Golding, which are much more mellow. Unfortunately, the best quality hops have the lowest alpha-acid content, so much larger quantities of these are required to achieve an equivalent degree of bitterness. This is considered to be uneconomical and extravagant by the breweries.

The poor flavour and aroma of high-alpha hops is not considered to be terribly important by many breweries because some of the flavour and aroma content of the hop is driven off during the boil, although the bittering remains. It is conventional to restore these lost components by adding a quantity of aroma hops to the copper during the last fifteen or twenty minutes of the boil. This is known as fare hopping.

Late hops

Late hops are hops that are sometimes put into the copper during the last fifteen minutes of the boil to restore the hop aroma; some of which has been driven off during the main part of the boil. The hops used at this stage should be of a type and quality commensurate with the type of beer being brewed, preferably the very best quality aroma hops. The Beta-acid and essential oil content are considered to be of prime importance at this stage. A quantity of high-quality aroma hops, equivalent to about 20-25 per cent of the main batch, is usually employed for this purpose. Late hops do not contribute much bitterness to the brew because the short boiling period which they receive does not give enough time for much of the bitterness to be extracted. Lagers are not usually late hopped because are not supposed to have a strong hop aroma.

Dry Hops

Dry hopping is the term used to describe the practice of adding a few hop cones to the cask after filling. This will add a hop aroma to the beer but does not add to the hop bitterness. The only important characteristic of hops used for dry hopping is the aroma imparted, which is contributed by the essential oil content. Therefore, the hops used at this stage should be specially selected to impart a first-class aroma, and should be the very best quality aroma hops, preferably Goldings or Fuggles. High-alpha copper hops should not be used for dry hopping because they impart a harsh aroma to the ale which becomes more unpleasant as the ale ages. It should be clear that dry hopping only improves the 'hoppy' aroma, it does not (and can not) increase the bitterness of the finished beer.

An alternative to dry hopping practised by many home brewers and some commercial brewers is to add a handful hops to the wort at the very end of the boil and leave them to soak for half an hour before the wort is cooled.

Types of hop

There are a very large number of varieties of hop that have been available in the past. However, the last ten years or so have seen a large increase in the number of specially developed varieties available to the grower. Recently these new varieties have become much more prominent and to a large extent have displaced many of the more traditional varieties of hop. These new vaneties have been developed to provide higher yields, different proportions of alpha-acids and essential oils, resistance to the most troublesome hop diseases, and suitability to mechanised harvesting. Wye College in Kent is responsible for the development of many of these new varieties, and Wye-developed hops now dominate the hop gardens of the world. Like the brewers, the hop growers have their own broad classifications for the hops they grow, namely: High-alpha hops, aroma hops, and general purpose hops.

Bittering (high-alpha) hops

High-alpha hops are the most economical bittering hops. These are usually hybrids, bred specially for high alpha-acid content and high yields in the hop garden. The high yields make them cheaper to buy and their high alpha acid content make them economical to use in the copper. These hops are usually employed for bittering purposes and are added to the copper at the beginning of the boil.

Aroma Hops

Aroma hops are those varieties of hop that are considered to have a fine flavour and aroma. Although aroma hops can be used as bittering hops, and the best quality beers employ aroma hops for bittering, they are low in alpha acid and yield. They are therefore more expensive to use as such. In general, aroma hops are usually employed as late hops, being added to the copper in the last fifteen minutes of the boil, or as dry hops added to the cask after filling.

Goldings and Fuggles are considered to be the finest aroma hops, but they have low yields, low alpha acid and low disease resistance, and are therefore more expensive to use. Many breweriesuse the new general-purpose hops for all or part of their aroma.

General-purpose hops

These are usually hybrid varieties which have been developed specially for high yields and dis-ease resistance, but which have a moderate alpha-acid content and a sufficiently delicate aroma to be used as. a bittering hop or aroma hop. They are dual-purpose - a case of being jack of all trades, master of none.

Challenger is the most common general-purpose hop used in this country, followed closely by Northdown. Northdown is a replacement for the old Northern Brewer varieties. Challenger and Northdown have the lowest alpha acid content of the new hybrid varieties, and I would suspect that these will eventually completely replace the traditional Coldings and Fuggles as aroma hops.

Golding

The term "Golding" seems to refer to a class of hop today rather than an individual strain Nevertheless, the Golding is one of our traditional varieties of hop and has been around for about two hundred years. The Golding has a very fine flavour and aroma and is considered to be Britain's premier hop. The Golding is highly susceptible to wilt, but it is grown successfully in the wilt-free areas of East Kent, Herefordshire, and Worcestershire. Goldings are not often used alone as copper hops due to their high price and low alpha-acid content, but are more often blended with other hops or used as late hops. The Golding is considered to be the best hop for dry hopping pale ales and bitters, for which it finds its major application. I would be surprised if the original Golding strain is still grown today. There are a number of varieties of hops that are classed as Goldings, and they are probably what we end up with; not the original strain with the fine aroma that made English pale ale famous. The Golding is regarded as an aroma hop.

Golding varieties

To add to the confusion surrounding hops, Golding varieties are not Goldings but a separate class of hop. Golding varieties have some Golding in them because they are cross-bred with Golding and other strains, but they do not exhibit true Golding characteristics. The only Golding variety that we are likely to come across these days is Whitbread's Golding Variety, however, this is classed as a Fuggle replacement. Likewise, Styrian Goldings are a Fuggle strain, grown seedless in central Europe.

Fuggle

The original Fuggle was introduced by a Mr Richard Fuggle of Brenchly in 1875. It is consid-ered to be Britain's second best hop, second only to Golding, and at one time it was Britain's most popular hop. It was used extensively in the darker beers, milds and stouts, but was often used as a late hop in pale ales and bitters. Again the Fuggle is susceptible to wilt and has a fairly low yield per acre. With the decline of the darker beers the Fuggle's importance is now giving way to the more modern wilt-resistant varieties of hop. The Fuggle is highly prized for its arom and is stilt used as a dry hop in traditional English ales, milds and bitters. However, the acreage devoted to the Fuggle is declining yearly and it looks set to disappear altogether in the near future. It currently accounts for less than ten per cent of total hop production as opposed to eighty percent in 1950. The Fuggle is considered to be an aroma hop.

Bramling cross

The Bramling Cross is still grown in small quantities and some published home-brew recipes still call for it, particularly those of the late Dave Line. It was originally developed as a wilt-resistant Golding replacement in the 1960's, and eventually became very popular. However, these days it accounts for about 1.5 per cent of the total hop harvest, and seems to have stabilised at that figure. It is considered to be an aroma hop.

Bultion

The Bullion is one of the earliest of the Goldings varieties; crossed with American stock. It is not classed as a Golding because its flavour and aroma are very unlike a typical Golding hop. The Bullion produces its own distinctive and fairly powerful "American" flavour which was never particularly popular with British brewers. It is a heavy cropper high in alpha-acid content, and was mainly used as an economical copper hop when blended with other varieties, or as a source of hop extract. In more recent times it has been displaced by the more modern wilt-resistant varieties of high alpha-acid hop, such as Target. Bullion accounts for only about one per cent of the hops produced, and its acreage is declining yearly.

Challenger (Wye)

Challenger is a Wye College hop which has rapidly gained popularity in recent years. Challenger is high in essential oils and is considered to be a general purpose hop. It has a good aroma and can be usefully employed for copper hopping, late hopping, or dry hopping. It is Britain's second-most popular hop.

Northdown (Wye)

Northdown is another of Wye College's children, a Northern Brewer derivative, which it has largely replaced. It has good flavour and aroma and is, therefore, a general purpose hop, suitable as a copper hop, late hop, or dry hop. It is Britain's third-most popular hop.

Northern brewer

Northern Brewer is one of the early varieties of hybrid hop. Like many other hops, the Northern Brewer is being displaced by more modern varieties, in this case Northdown which is similar to Northern Brewer. Northern Brewer is almost extinct these days. It is considered to be a general-purpose hop.

Omega

Omega is the most recent of the new hop varieties, introduced in the mid 1980's. However, Omega is still in its formative years. Hop gardens take years to mature so it is too early to tell how popular it will eventually become. However, it already features in some commercial brewery recipes, notably Courage, so it seems to have got off to a fairly good start. Omega is considered to be a bittering hop.

Progress

Progress was introduced in 1966 as a wilt-tolerant Fuggle replacement bred from Whitbread's Golding Variety. However, like most other Fuggle replacements, the acreage devoted to it is rapidly diminishing. It is not holding out too well against other varieties and it now has the lowest acreage of any hop. It will probably become extinct during the currency of this book. It is considered to be an aroma hop.

Target (Wye)

Target is the result of a breeding programme by Wye College in Kent to produce a variety of hop that is resistant to both wilt and powdery mildew. Target has a high alpha-add content, is resistant to verticillum wilt, and immune to the most common races of powdery mildew. Target has become Britain's most important hop, accounting for about forty per cent of Britain's hop production. It has a very high alpha-acid content and therefore finds apphcat.on mostly as a high-bittering hop. Although it is grown seeded, Target has a very low seed content. Target is not considered to be a good aroma hop and should be used purely for bittering.

Whitbread Golding Variety. (W.G.V.)

Whitbread Golding Variety is not a Golding. It is a hybrid, with Golding as one of its parent strains. However, ills classed as a Fugglcs substitute. Like most other Fuggle substitutes, its pop-ularity is giving way to new varieties of hop. It currently accounts for about three per cent ot hop production and is classed as an aroma hop.

Yeoman (Wye)

Yeoman was introduced by Wye College in 1980. It is very similar to Target in both composi-

tion and disease resistance, but its aroma is more mellow, making it suitable for lager beers as well as traditional ales. Yeoman is considered to be a Uttering hop.

Zenith (Wye)

Zenith is a relatively new hop introduced in the early 1980's. but, as yet, does not seem to be particularly popular with commercial brewers. Zenith is high in essential oils, particularly when grown seedless. The aroma imparted is fairly good, but Zenith is considered to be a bittering hop.

Seedless hop varieties

Continental beers traditionally use seedless hops and therefore most hops grown on the continent of Europe are grown seedless. This is done by eliminating all the male plants in the area. However, the British export large quantities of seeded hops to Europe, so the Continentals are quite happy to use seeded hops when the fancy takes them. Seedless versions of Target, Yeoman, Zenith, Challenger, and Northdown are grown in England. Target and Northdown being the most popular. They are probably grown for export or for Anglo lagers.

Imported seedless hops are available to the home brewer. The best quality continental hops are reputed to come from the Saaz area of Czechoslovakia, the second best from the Spalt area of Bavaria, followed closely by hops grown in the Hallortau region of Bavaria. Styrian Goldings are a Fuggle variety grown seedless in former Yugoslavia.

However, the terms Saaz, Spalt, and Hallertau refer to hop growing regions and not the actual variety of hop. To simply refer to hops as being Saaz or Hallertau may have been appropriate fifty years ago, as indeed hops in this country were simply referred to as Kents, East Kents, or Worcesters, but these days it is an over-simplification. For instance, Hallertau, the largest hop growing region in Europe, grows a number of varieties of hop. Apart from its traditional vari-eties, it also grows a number of English varieties, such as Northern Brewer, Northdown, and Goldings, plus a range of its own modern disease-resistant hybrids.

I suspect that we can rely upon the importers and hop merchants to provide us with a true continental lager hop, not an English variety that happens to be grown in/the region. There is no point in importing coal to Newcastle.

Hop storage

Hops are not very stable during storage and must be stored carefully if the quality of the hop is to be maintained. Hops can oxidise very quickly during storage and they are also photosensitive. Commercial hops are traditionally packed by mechanically compressing them into the traditional long hop pockets. This high degree of compression helps to exclude air from the bulk of the hops and so retard the oxidisation. Furthermore hops are always stored in a cool environment and in the dark, which also retard the oxidisation process. Hop merchants and commercial brewers keep their hops in cold store under carefully controlled conditions, just above freezing point, which enables them to remain in good condition for several years.

The Photosensitivity of hops is an important degradation factor. Hops are harvested and are at their best just before they fully ripen. Exposing hops to sunlight, or any source of light at the correct wavelenth, will cause the ripening process to continue and degrate the hop. As an analogy, tomatoes that have been picked green will continue to ripen if exposed to sunlight, but an over-ripened tomato will degrade and start to go squidgy. The same principle applies to hop. The great breweries of old took great pains to ensure that the hops were never exposed to direct sunlight; even while they were waiting to go into the copper. The copper rooms of breweries were often equipped with large canopies, under which the hops were held in readiness for the copper, and which shielded the hops from sunlight coming through the rooflights. This photosensitivity of hops is carried through to the finished beer. The reason for beer being traditionally supplied in dark bottles is to prevent the beer from becoming sun-struck, and not, as is commonly believed, to hide its murky contents from the hapless imbiber. A sun-struck beer has unpleasant off-flavours. Exposure to fluorescent lights can cause hop degradation or a sun-struck beer in a very short time.

Some of the hops supplied by the home-brew trade are in a sorry old state. I have come across dull, brown, lifeless specimens which are dry and brittle, the resins having hardened, making them of little brewing value and zero "aroma" value. They are often loosely packed in inadequately thin, flimsy, polythene bags which contain as much air as hops; an open invitation to premature oxidation and deterioration. To make matters worse, they can be found stored on open shelves in a warm shop exposed to direct sunlight or under fluorescent light. A commercial brewer would laugh if he saw the quality of hops that we were expected to work with.

Ideally, the hops supplied to us should be high-quality true-to-type hops, tightly packed in hermetically sealed bags, either under vacuum or under nitrogen. They should be adequately labelled with the variety of hop, the region in which they were grown, their alpha-acid at harvest, and their harvest date. In the shop they should be stored in a cool place and in the dark.

Proper examination of hops is an expert's job, but they should be bright and yellowish-green in colour; unripe hops are excessively green. They certainly should not be brown which indicates badly stored or sun-struck hops. They may be predominantly yellow if they have been sulphured, but the sulphuring of hops seems to have fallen out of fashion these days. They should be properly packed, as described above; and upon opening they should have a strong aroma and a resinous sticky feel. However, do not be tempted to open hermetically sealed packets until you are ready to use them.

When storing hops at home, close the bags tightly so that they are air-tight and keep them in the coolest place you can find, but not in a place where they are likely to freeze. Packets of hops can be slipped into black plastic bags to exclude light.

Old hops

There is nothing inherently wrong with old hops unless, of course, you were expecting to buy new ones. Old hops which have been properly stored still retain their preserving power and much of their bittermg power, but the bittering becomes less harsh and their flavour and aroma becomes more mellow. Some breweries, particularly continental ones only use three-year-old hops for this reason. Many of the new varieties of high-yield hops, which have a harsh flavour and objectionable aroma when new, can very often be quite acceptable after they have aged a year or two. At one time British breweries blended hops of three or four different years; some still do. This was done to buffer the differences experienced in hop characteristic from harvest to harvest or from grower to grower, so that the beer did not suddenly change character when a new batch of hops came in.

However it would be difficult for the amateur brewer to properly judge aged hops. Obviously hops that have been stored by a hop merchant at just above freezing point in his cold store would change less than hops stored in any other way. Obviously, hops stored under different conditions would show different characteristics. The actual age of a hop will not be the same as its perceived age. However, the concept is worth thinking about if you wish to brew a delicately flavoured beer.

Hop pellets

Hop pellets have been around for one hundred years or more, but it is only relatively recently that have found any wide acceptance. They are made by pulverising hops into a powder and then compressing them into pellets. They have more stable storage characteristic than whole hops due to the pelletisation process preventing air from gaining access to the centre. Only the outside of the pellet could be exposed to the atmosphere, but this is eliminated by vacuum packing the pellets or packing them in an inert nitrogen atmosphere. Nowadays commercial breweries tend to use hop pellets rather than whole hops. In fact, hop pellets account for more than seventy per cent of Britain's hop consumption. They are not used much in home brewing because whole hops are more appropriate to the home-brew set-up and are more traditional.

In a traditional brewery that uses whole hops, the hops settle on to a perforated floor at the bottom of the copper, or a separate vessel called a hop-back, and act as a filter bed to filter out the trub and other extraneous matter generated by the boil. In this way spent hop debris and trub are left behind in the hop-back, giving a clear and bright wort. If this rubbish is not removed and is carried across to the finished beer, the trub can cause clarity and stability problems and the hop debris will develop a tannic bitter taste with age, caused by the woody strigs and other parts of the hop.

The use of hop pellets presents a problem. They disintegrate into a powder during the boil and therefore cannot act as a filter bed to filter out the trub. Commercial brewers that use hop pellets have an additional piece of equipment, known as a whirlpool; which removes the hop debris and trub. There is nothing particularly complicated about this apparatus; it is simply a cylindrical tank with tangential inlet and outlet pipes fitted in the sides of the tank near the bottom. The tank is filled via the inlet pipe which, being tangential, sets the wort slowly revolving in the manner of a whirlpool, hence its name. The trub and hop debris are drawn Into the eye of the whirlpool and settle in a neat little pile in the centre of the vessel, The trub, being composed of gummy particles, stick together and stay put on the bottom. When sufficient time has elapsed for the debris fo settle, usually half an hour to one hour, the clear wort is drawn off via the outlet, which is again tangential to maintain the rotating motion of the wort, Commercial breweries go to the extra expense of a whirlpool and use hop pellets because the system lends itself more readily to automatic cleaning procedures. The trub and spent hop powder can simply be rinsed out of a whirlpool, whereas with a traditional brewery using whole hops, someone has to get into the hop-back and physically shovel out the hops, The shovelling of hops by people who have to be paid wages is frowned upon by brewery accountants. Also the following brew is held up while this shovelling is taking place.

Hop pellets are available from home-brew shops even though we do not normally have whirlpools. However, they can be used in home brewing provided that the possible limitations of using them are properly understood. However, these limitations are more theoretical than practical. The possibility of trub getting carried across to the wort is not considered to be a particularly serious problem by many home brewers. The benefits of removing trub are more apparent to the commercial brewer than the home brewer in the form of improved shelf life.

Pellets would be particularly valuable to home brewers who do not have the time or inclination to construct a hop-back or similar apparatus.

Hop pellets from different sources vary slightly in their concentration, but in gereral twenty per cent less pellet hops are required when compared to their whole-hop counterparts.

Alpha-acid content of hops

The primary standard by which a hop is judged is its alpha-acid content. The alpha-acid content of a hop is a measure of its bittering power; the beta acid and the essential oil content of a hop constitute its aroma and flavour-giving properties. Unfortunately these three components do not complement each other. High-alpha hops are often used in the copper to provide economical bittering power, but high-alpha hops do not usually have a pleasing aroma. Different varieties of hop impart different degrees of bitterness and different hop flavours and aromas. Some varieties of hop are twice as bitter as other varieties, and the flavour and aroma of some varieties of hop are attractive whereas with other varieties of hoo it is objectionable. To confuse matters even further, the bitterness of a particular hop will vary from crop to crop, and from harvest to harvest.

Immediately after the harvest the alpha-acid content of every batch of hops is measured and this information is supplied to the commercial purchaser as the basis on which to determine the quality of the hops, comparative hopping rates, and ultimately the market price. Obviously if a batch of hops has a lower alpha-acid content than the previous batch, the brewer will need to use more hops to achieve the same bitterness in his beer and will obviously not be prepared to pay as high a price for them. The other constituents, beta-acids and essential oils, are considered to be present in the same ratios as the alpha-acids, and they would also be down on the norm.

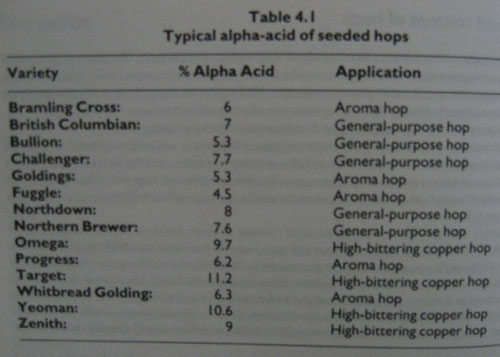

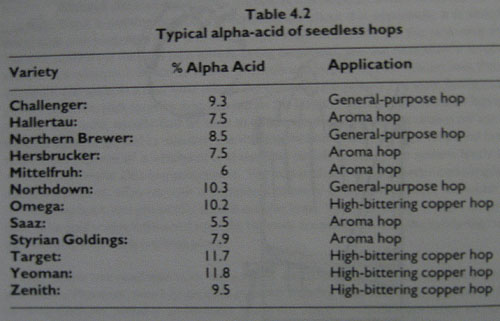

The typical alpha-acid content of the most common varieties of hops are listed in the tables below. The first table is for seeded hops, the second for seedless.

Typical alpha-acid of seeded hops

Typical alpha-acid of seedless hops

Challenger, Northdown, Omega, Target, Yeoman, and Zenith are English varieties of hop which are normally grown seeded, but smaller quantities of seedless versions of these art also grown in Britain. The alpha-acids vary slightly between seeded and seedless versions, hence they are shown in both tables. Samples of these varieties found in home-brew shops will almost certainly be seeded unless the packet states otherwise. If in doubt you can easily check whether or not the samples contain seeds. However, the high-alpha or high-bittering varieties of these have such a low seed count that the difference in alpha-acid between seeded and seedless versions is minimal.

Using different varieties of hop

The range of hops available through home-brew wholesalers at the time of writing is fairly good, particularly when one considers that most published recipes simply call for Goldings or Fuggles, or similar traditional varieties. However, there are about twenty varieties of hop available in this country, many more if one takes regional variations into account so it would be unfair to expect our shops to stock the whole range. There will be times when you will need to substitute one variety of hops for another, either because the specified hops are not in stock, or simply because you wish to experiment or use hops that you already have. Unfortunately, a direct weight-for-weight substitution will not provide the same level of bitterness, but a simple calculation will reveal the proper quantity of hops to use.

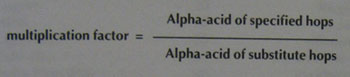

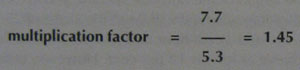

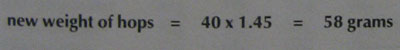

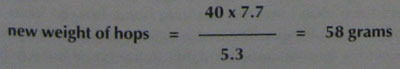

Assuming that you wish to maintain an equivalent level of bitterness, a simple comparison of the alpha-acid ratios of the two hop varieties will provide the new quantity of hops If your recipe calls for 40 grams of Challenger, but you wish to use Goldings instead, the following simple relationship is all that is required.

Challenger has an alpha-acid of 7.7 per cent and Goldings have an alpha acid of 5.3 per cent. The sum then becomes:

To obtain the new weight of hops simply multiply the quantity of the specified hops by the factor, thus:

Alternatively, using the same figures in a single formula:

As a rule of thumb when experimenting with different varieties of hops, the low alpha-acid varieties are considered to be the best quality hops, but they are less economical because more of them need to be used for a given level of bitterness. The economics of different varieties of hop are only of concern to the commercial brewers, and should not be of any consequence to home brewers.

European Bittering Units (EBUs)

European Bittering Units or, less parochially, International Bittering Units are a world standard method of assessing the bitterness of beers. As the rest of the brewing world uses EBUs as an indication of bitterness, it seems appropriate that the home-brew hobby should follow suit.

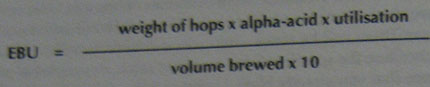

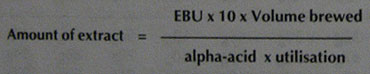

The bitterness of a beer in EBUs is given by:

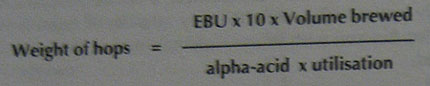

To find the weight of hops required in order to produce a given bitterness in a given volume of beer the formula can be re-written thus:

Where:

Volume: is in litres

Weight: of hops is in grams

Alpha-acid: of hops is in per cent

Hop utilisation: is in per cent

Hop utilisation

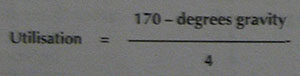

The hop utilisation figure in the equation corresponds to the efficiency of the boil and is dependant upon many things: the vigour of the boil, the length of the boil, the specific gravity of the wort, and the equipment used. In general the utilisation achieved will be in the range of 29-35 per cent under ideal conditions with a vigorous one-and-a-half hour boil and the hops boiling freely in the wort. Some commercial brewers achieve as low as 18 per cent. However, utilisa-tion is a complex matter, not only is utilisation efficiency dependant upon the specific gravity of the wort, but the actual efficiency achieved varies considerably from brewery to brewery. Commercial brewers use the following equation to approximate utilisation efficiency:

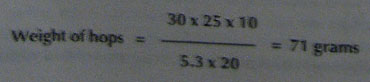

Where degrees gravity is the original gravity of the final beer in degrees, i.e., 1045 = 45 degrees. However, when using this equation 1 have found that the resulting home-brewed beers are usually under-hopped. There are various reasons for this. The first is that the utilisation equation is only a rough apptoximation, the second is that the hops available in the home-brew hobby have nothing like the freshness of commercially available hops, and the third is that home-brewed beers are usually hoppier than commercial beers. Also, home brewers use a wide range of brewing methods giving different degrees of efficiency. To overcome these problems it is best to assume the lowest probable utilisation efficiency of 20 per cent. This gives hop rates closer to the home brew norm. All of the recipes in this book assume an efficiency of 20 per cent. The quantity of hops required to achieve 30 units of bitterness in 25 litres of beer using Golding hops at an alpha-acid content of 5.3 per cent, assuming a utilisation of 20 per cent, is as follows:

Home brewers do tend to use much higher hop rates than commercial brewers. The perceived bitterness of a beer is a subjective assessment, and such things cannot be quantified in a rigid mathematical manner. Brewers are continually jiggling their hop rates to maintain a consistent perceived bitterness. Until the British home-brewing industry gets around to printing on their packaging the measured alpha-acid of the hops that they supply, such calculations will always be approximate.

EBUs apply only to the bittering hops, i.e., the hops that are put into the copper at the beginning of the boll. Late hops do not contribute much bitterness to the wort due to the shorter dwell time in the copper. They only restore aroma which has been lost in the boil.

Late hops are generally 20-25 per cent of the quantity of bittering hops employed and the exact amount is determined by experience and personal preference.

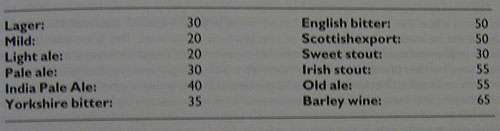

Typical bitterness of various beers in EBUs

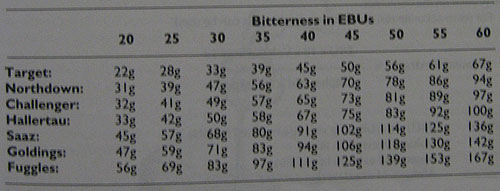

Typical hop quantities in grams for 25 litres at 20% efficiency

This table is based upon the published avarage alpha-acid of the hops, and will be approximate by definition. More accurate results will be obtained using the formulae provided above, in conjunction with the actual alpha-acid of the hop, which by rights, should be printed on the packets.

Liquid hop extracts

Hop extracts have been around for a number of years, however some confusion exists among home brewers as to their proper application. There are two basic types or hop extract, one of these contains alpha-acid and is used to adjust the bitterness of a brew, and the other contains hop oils and is used to provide a "hoppy" aroma. These two basic types of hop extract, one of two forms, soluble and non-soluble. The non-soluble types are the extracts supplied in their raw state and, for proper utilisation, should be mixed with the wort prior to boiling. The other types have been specially processed to make them soluble in water and can be added to the beer at any stage of production. It is the soluble types that are most useful to the home brewer.

Isomerised hop extract

Isomerised hop extract contains the natural bittering components of the hop converted into a water soluble form. The alpha-acids (humulones) have been converted by an industrial process into isohumulones, that is, they have been isomerised or converted into a water soluble form.

Unlike ordinary hop extract, isomerised hop extract does not need to be boiled into solution; being water soluble it can be used at any stage of beer production. It can be added to the boiler, fermenter, barrel, or even to your pint pot if the fancy takes you. However, only isomerised hop extract is soluble in beer. Non-isomerised types have to be boiled with the wort and therefore offer no advantages to the brewer over using whole hops or pellets.

The main application of isomerised hop extract is in beer kits, or to make increases in the bitterness of a beer that has not turned out to be not as bitter as intended. Isomerised hop extract should not be used as the sole source of hop products in the wort. This is because brewer's yeasts require some additional hop material to be present for proper behaviour to occur, and there are a number of important flavour reactions which take place during the boil. The manufacturers recommend that a maximum of 50 per cent of the bitterness is supplied by extract.

Isomerised hop extract supplied to commercial breweries contains up to 30 per cent alpha-acid, but the extract supplied via the home brew trade is usually adjusted to around 5 per cent alpha-acid. It is adjusted so that 5ml or 1 teaspoonful of extract conveniently increases the bitterness of 5 gallons of beer by 10 bittering units. The percentage alpha-acid contained in the extract will vary from supplier to supplier, but in any ease, the percentage of alpha-acid should be printed on the container.

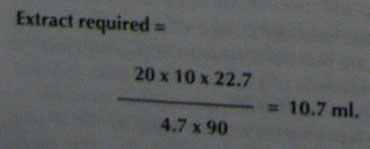

For more accurate results the following formula can be used:

Where:

EBU: is the bittering increase required in EBUs

Volume brewed: in litres

Amount of extract: in milliliters

Alpha-acid of extract: in per cent

Utilisation: in per cent

The utilisation efficiency of hop extract is between 85 and 95 per cent, and is mainly dependent upon the type of water used for brewing. Hard water gives a poorer utilisation than soft water.

To find the amount of extract required to increase the bitterness of 5 gallons (22.7 litres) of beer by 20 EBUs, assuming a utilisation of 90 per cent and using isomerised extract containing 4.7 per cent alpha-acid:

The isomerised hop extract can be measured with a graduated syringe or estimated using a measuring spoon. A domestic teaspoon holds about 5ml. It should be mixed with a little water before being added to me beer. Soft water, distilled water, or de-ionised water is best, but water that has been boiled in a kettle and allowed to cool is satisfactory. It should not be added to the beer without dilution, and beer should not be used for the initial dilution.

Isomerised hop extract can be added at any stage of beer production but the most convenient place is probably to the fermenting vessel at the end of fermentation, where overall bitterness can be judged and where it can be properly mixed into the beer. It can also be added directly to the cask, along with the primings and a few dry hops if desired, but it should be added and mixed into the beer before any finings are added.

Isomerised hop extract only supplies bitterness to a beer, it does not supply hop aroma or flavour, this must be supplied from elsewhere, either by the use of hop aroma emulsion, or by boiling real hops at the brewing stage.

Hop aroma extracts and emulsions

Aroma extracts are extracts of hop oils which provide the hoppy aroma to beers. They do not impart bitterness. Hop aroma emulsions are these extracts in water soluble form. They can be used at any stage of the brewing process, but it should be remembered that the essential oils of hops are volatile and will be driven off if they are subjected to a prolonged boiling period. Hop aroma extracts do not offer any advantages over dry hopping with whole hops as far as the home brewer is concerned, but they can be useful for making late corrections to aroma. Follow the supplier's instructions.

Read also:

Ingredients for brewing: grain, sugar, malt extract

Traditional Commercial Brewing

Home Brewing. Beginners Start Here

All You should Know about Brewery Yeast